Dr. Evelyn Steinhauer is Associate Dean, Indigenous Education and a Professor in the Department of Educational Policy (Faculty of Education) at the University of Alberta, specializing in Indigenous Peoples Education.

Evelyn is actively engaged in many community-based research initiatives and sits on various committees on and off campus.

Born in Alberta, and a member of the Saddle Lake Cree Nation, Evelyn completed her undergraduate degree with Athabasca University at University nuxełhot’įne thaaɁehots’į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills (formerly Blue Quills First Nations College); a Masters of Education Degree, and a PhD at the University of Alberta through the Department of Educational Policy Studies in the Faculty of Education.

A mother of two grown daughters, a grandmother of 11 and a great grandmother (otanskotapan) of two.

Topics of Interest

Evelyn has had the opportunity to conduct research and literature reviews on several topics that are of special interest to her. Some of these topics include:

Aboriginal/Indigenous Teacher Education Programs. What are the experiences of teachers that go through these programs, and what are their experience as they begin their teaching practice?

School choice in First Nations communities. Why are so many of our parents opting to send their children off-reserve to attend provincial schools, when they have the opportunity to send their children to their schools on reserve?

Aboriginal student experience. What are their experiences in the K-12 school system, in postsecondary, and in higher education?

Government policy and the implications on Aboriginal education. What impact do these policies have on our children?

Tribal Colleges: What are the factors that contribute to the successes of Native students within the Tribal College system?

Barriers to success: What are the obstacles preventing Native students from participating in post-secondary programs?

Issues in First Nations Education. What are the issues?

Indigenous Research Methodologies: What is Indigenous knowledge? How might we incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing into the postsecondary student experience.

The impact of residential schools on the Aboriginal family system.

Oral tradition as a way of knowing.

Indigenous Language, particularly nehiyawiwin. How does having our language contribute to student achievement? Why must we re-learn our languages?

Conversational Cree

Listen and Learn with Windspeaker Radio's Conversational Nêhiyawêwin, for a fun half-hour of Cree words, stories, music and lots of laughs.

Hosted by Jim Cardinal & Evelyn Steinhauer.

Hear new shows Wednesday mornings at 10:00 AM on CFWE 98.5 FM Radio or Wednesday at 11:00 AM on The Raven 89.3 FM.

This program made possible by the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Dr. Steinhauer’s passion is Indigenous Education and evidence of this is revealed in her doctoral dissertation published in 2008.

This work addresses the topic of parental school choice on First Nations reserves and looks at the reasons that guide First Nations parents in their decisions to send their children to off-reserve or on-reserve schools. Dr. Steinhauer’s writing not only reveals the reasons for parental school choice in First Nations communities, but also discloses pertinent and significant information about what life “is really like” for many Indigenous children that attend school off-reserve.

Those who came before…following in their footsteps

Background Image

Norway House, Manitoba

The Canadian Encyclopedia

A Ukrainian Connection

The unusual story of one Alberta pioneer family reveals how misfortune could change the people’s lives in the most dramatic and unforeseen ways. . . . A Ukrainian farmer near Andrew lost his wife when she was giving birth to their sixth child, a baby boy. The blow was especially severe because the winter had been long and difficult, and the family was reduced to eating a thin gruel made of wheat. A week after the woman’s death, the husband was working outside . . . when he heard a gunshot from a remote corner of the land. Investigating, he came across a hunting party of Cree Indians, one of whom spoke Ukrainian. The two men began talking, and the farmer explained the unfortunate situation that he and his children found themselves in. When the Indian asked why he did not hunt to supplement their meager diet, since game was plentiful in the area, the farmer replied that he was so poor he did not even own a gun. They continued talking, and after a while the farmer made a desperate proposition. Realizing that the newborn would probably die without a mother, he suggested that the Indians take the baby with them in exchange for one of their guns. The oldest children would remain with their father, as they could look after each other and also be of help to him.

Sympathetic to the man’s plight, the hunters agreed and took the week-old child with them to be raised by the women of the Goodfish Lake Reserve northeast of Vilna. By the time the father tried to persuade him to rejoin the family near Andrew, the boy—now named Steve Whitford—had become so accustomed to his adopted lifestyle and people that he refused to go, and answered in Cree, “I’m an Indian.” Whitford eventually became one of the most respected members of the Goodfish Lake community in which he married, living outside the perimeter of the reserve (since he was never legally recognized as an Indian). (p. 116)

On my mother’s side I have been able to trace my ancestry back to only my grandfather, Steve Whitford, born Steve Koroluk in 1907. His story has been recorded in Balan’s[1] (1984) Salt and Braided Bread: Ukrainian Life in Canada, and is as follows:

[1] Jars Balan is widely known as an author and editor. In addition to the abovementioned book, he has edited numerous books and periodicals dealing with Ukrainian Canadian themes and produced scholarly and popular articles on a broad range of Ukrainian Canadian topics over the years (Balan, 1984).

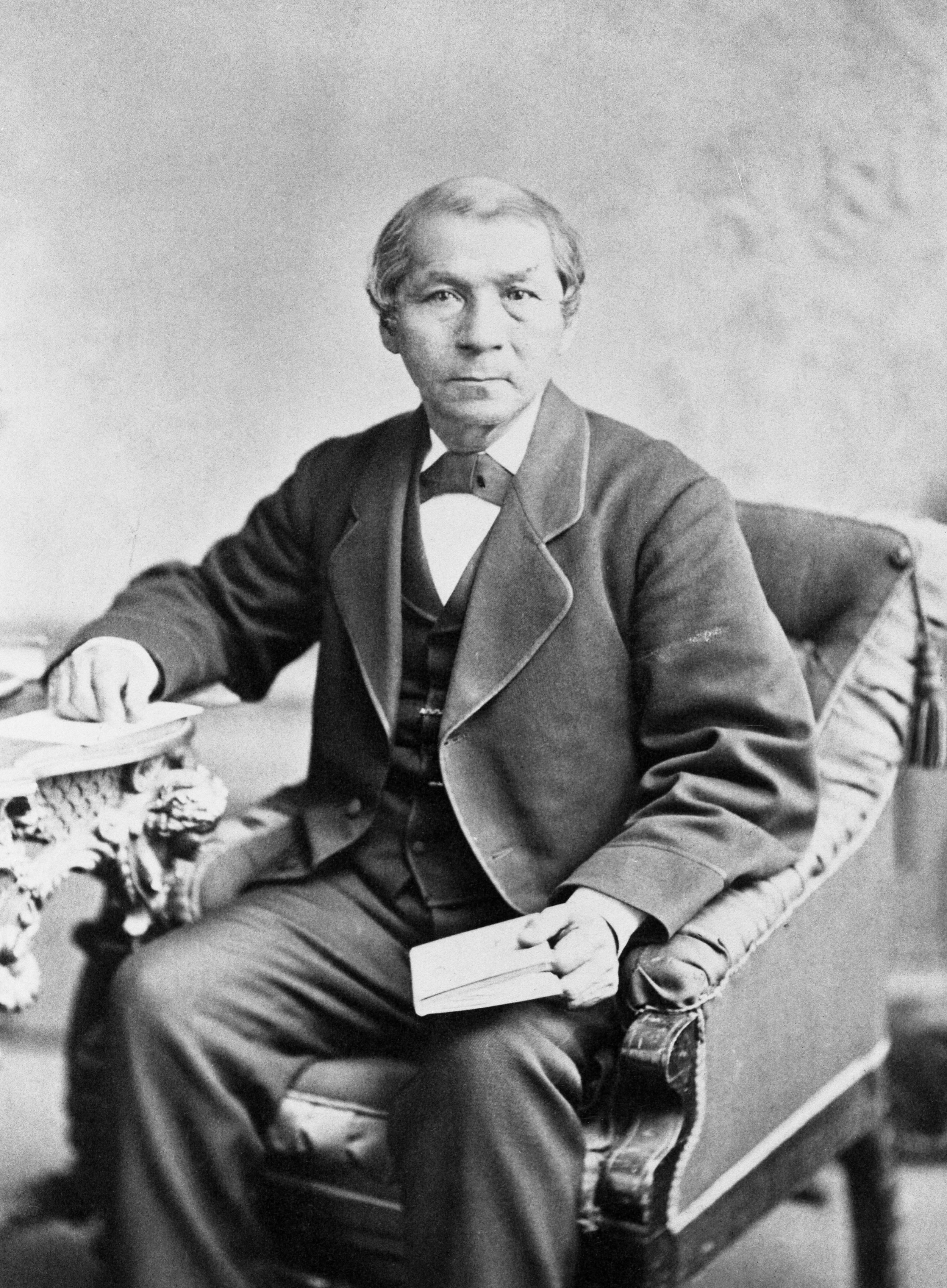

Henry Bird Steinhauer

STEINHAUER, HENRY BIRD (probably also known as Sowengisik, and may originally have been baptized as George Kachenooting).

Methodist missionary, school teacher, and translator. Born probably c. 1818 in Upper Canada near the present Rama Indian Reserve. Eldest son of Bigwind and Mary Kachenooting. Married 5 Aug. 1846 Mamenawatum (Seeseeb, Jessie Joyful) at Norway House (MB), and they had five daughters and five sons (a great-grandson, Ralph Steinhauer, was lieutenant governor of Alberta from 1974 to 1979).

Died 29 Dec. 1884 at Whitefish Lake (AB).

The Ojibwa who became Henry Bird Steinhauer in 1828 was probably originally named Sowengisik. He took the new name after Methodist missionary William Case found an American benefactor who agreed to provide for the education of an Indian youth if that youth adopted his name. It is possible that Steinhauer was also the person baptized as George Kachenooting by Case earlier in 1828, on 17 June, at Holland Landing, Upper Canada. Steinhauer attended the Grape Island school at the south end of Lake Couchiching from 1829 to 1832, and the Cazenovia Seminary in Cazenovia, N.Y., from 1832 to 1835. He was appointed by the Wesleyan Methodist Church to teach at the Credit River mission on Lake Ontario in 1835, and the following year Egerton Ryerson enrolled him at the Upper Canada Academy in Cobourg. His studies at the academy were interrupted for the year 1837–38 by an appointment to teach at the Alderville mission school in Northumberland County, Upper Canada, to which he returned after he graduated in 1839, at the head of his class.

In 1840 Steinhauer was dispatched to Lac La Pluie (Rainy Lake, Ont.) where he assisted the Reverend William Mason as translator, interpreter, and teacher. Two years later, at the request of missionary James Evans, he was sent to Rossville mission near Norway House. Evans felt that Steinhauer would readily master Cree because he spoke Ojibwa, which belongs to the same language group, and would thus be able to assist him in translating the Bible and hymns into his system of Cree syllabics. Steinhauer was the chief translator at Norway House by 1846. In 1851 he was asked to establish a Methodist mission at Oxford House (Man.), 200 miles northeast of Norway House, and he built the mission 20 miles from the Hudson’s Bay Company fort. In the fall of 1854 Steinhauer, who was then the only Methodist missionary west of Norway House, accompanied John Ryerson to England to publicize the western missionary work, returning the following spring.

Steinhauer was ordained at the conference of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada in London, Canada West, in June 1855, and on the 8th of that month received news of his posting to Lac La Biche (Alta). He was not overly pleased with the posting and thought he might wish to return to the east for his children’s education. He travelled west with Thomas Woolsey, who was posted to Pigeon Lake (Alta). Although they were at the time the only Methodist missionaries in the northwest, they found that they were “surrounded by Romanists” and felt that they were “very closely watched by their two priests.” Lac La Biche was originally selected for Steinhauer “on account of its being out of reach of the enemy, the murderous Blackfoot,” but because he considered the location so removed from HBC posts, he did not encourage the development of a settled mission community there. He preferred instead to travel extensively among the Cree to carry out missionary activities.

The intense rivalry with the Roman Catholic missionaries at Lac La Biche, and the post’s isolation from the fur-bearing animals and the buffalo herds, led Steinhauer, during the early summer of 1858, to move his mission south to Whitefish Lake where there was a band of Cree. The location was ideal, with land suitable for agriculture and a lake abounding with fish. During the winter of 1859–60, when smallpox swept the prairies, Steinhauer temporarily moved the band as a quarantine measure, and no lives were lost. He further ensured the well-being of his mission by discouraging traders from establishing trading-posts in the area in order to reduce the influx of alcohol. In 1864 Steinhauer opened the first Protestant church in the region, at Whitefish Lake. Later that year his eldest daughter, Abigail, was married in the church to John Chantler McDougall, whose father, the Reverend George Millward McDougall, performed the ceremony. With George McDougall and Peter Erasmus, Steinhauer visited the Mountain Stonies that fall in an attempt to expand missionary work among them. Abigail was one of 16 people who died at Whitefish Lake during the smallpox epidemic of 1870. Such epidemics as well as poverty, hunger, and alcohol were continual problems surrounding mission work.

Steinhauer was appointed to Woodville, on Pigeon Lake, southwest of Edmonton, for the 1873–74 season. The Whitefish Lake mission was to be tended in his absence by Benjamin Sinclair, a local leader, but when he returned Steinhauer found it a shambles. Many families had moved away, fields were untended, and church attendance was down.

In an unusually critical letter to the Missionary Society of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Canada, published in 1875, Steinhauer wrote, “A foreigner either as a missionary or otherwise, will never take so well with the natives of this country . . . there is always a distrust on the part of a native to the foreigner, from the fact that the native has been so long down-trodden by the white man.” He referred to the immigration of whites into the west as a “blighting and benighting” influence and also criticized the missionary society for not heeding his pleas for essential materials. This letter represents a turning-point in Steinhauer’s appraisal of his role as a missionary to the Cree. Although he never ceased to maintain his religious convictions, he did become less of a traditional missionary by, in effect, severing his obligations to the missionary society and asserting his Indian identity.

Shortly after his return from a conference in Brandon, Man., in 1884, an influenza epidemic swept the North-West Territories and Steinhauer fell seriously ill. He died on 29 December.

Krystyna Z. Sieciechowicz

Dictionary of Canadian Biography

Background Image

St. Andrew’s Indian Residential School (Whitefish Lake, Atikameg, AB)

Algoma University Archives

Shawahnekizhek. Henry Bird Steinhauer: Child of Two Cultures - Melvin D. Steinhauer